Bournemouth’s biggest garden

Meyrick Park is one of the five parks which give Bournemouth its verdant lushness. Tony Burton-Page tells the story of an open space.

Published in February ’17

In John Betjeman’s 1949 essay ‘Bournemouth’ from the collection ‘First and Last Loves’, he describes the town as ‘a garden with houses in it’. He is warmly appreciative of it (although, typically, he did not approve of the ‘lengths of flashy chromium’ in the main shopping streets – even in 1949!), but he says ‘the beauty of Bournemouth consists in three things, her layout, her larger villas and her churches. All are Victorian.’ He attributes the beauty of the town’s layout to two of the most important figures in its history: Sir George Ivison Tapps and Benjamin Ferrey. Tapps was the Lord of the Manor of Christchurch, which meant that most of the land between Christchurch and Poole came under his ownership. He recruited the services of the Gothic church architect Ferrey to lay out his estate in line with the picturesque school of Georgian gardening, with no straight lines and much greenery.

But the origins of Bournemouth’s copious parkland go back further in time: to the Christchurch Inclosure Act of 1802, one of many acts of parliament which enclosed open fields and common land to create legal property rights over land that had previously been considered common. Parliament had decided that to leave the large amount of common land in the UK uncultivated was absurd, hence the passing of the General Inclosure Act in 1801; their thinking was undoubtedly influenced by the need to fund the war against France. In fact, the idea of private ownership of land is modern, only a few hundred years old: tribespeople and medieval peasants would not have understood the concept of one person possessing all legal rights to one stretch of land to the exclusion of everybody else – rather, they would have expected to enjoy ‘usufructory’ rights enabling them to graze stock, cut wood or peat, draw water or grow crops on what they regarded as ‘common’ land.

It was the possible loss of these rights which worried the inhabitants of the villages affected by the enclosure process. Inspired by the passing of the General Inclosure Act in 1801, local landowners, led by Sir George Ivison Tapps, had lobbied Parliament to enclose the areas of common land on Poole Heath, and this brought about the Christchurch Inclosure Act. Three Inclosure Commissioners were appointed to allocate the land enclosed and to make an Award. The anxious graziers and turf cutters from the villages approached William West, the farmer at Muscliff Farm, and asked him to represent their point of view to the commissioners, knowing that he was a well-educated man and would be taken more seriously by the officials than they themselves would have been. West had assumed the agricultural tenancy at Muscliff in 1800, having previously occupied land at Melbury Abbas. The cottagers took a considerable risk in walking to Muscliff Farm, for at that time the establishment was worried about gatherings of discontented workers. The Government had passed the Combination Laws in 1799 and 1800, which made it illegal for workers to gather together and discuss their working conditions – the penalty being imprisonment or transportation, as in the case of the Tolpuddle Martyrs in 1834.

West created a petition on their behalf, calling for ‘the apportionment of sufficient land to ensure the continued supply of turf for the needs of those formerly entitled to it’, and duly presented it to the Commissioners in Ringwood at their first meeting. Even in those days, the wheels of bureaucracy moved slowly, and the award was eventually made in 1805. They had taken West’s petition into consideration and ruled that 425 acres (172 ha) in five locations should be set aside in trust with the Lord of the Manor for the benefit of the occupiers of certain cottages ‘in lieu of their Rights or pretended Rights or customs in cutting Turves’. However, as more efficient types of fuel were introduced in the late nineteenth century, turf-cutting in these areas gradually died out, and these five ‘turbary commons’ eventually were acquired by the new Bournemouth Borough Council, becoming the parks which are today known as Queen’s Park, King’s Park, Redhill Park, Seafield Gardens and Meyrick Park.

Sir George Eliott Meyrick Tapps-Gervis-Meyrick, after whom the park is named, fortunately not in the entirety of his name

Sir George Ivison Tapps died in 1835, and his son Sir George William Tapps-Gervis inherited the estate. However, he survived his father by only seven years, the estate passing to his son, who was only 14 at the time. Like his father, he was subsequently required to use additional names to comply with the conditions of a will – in this case, that of a relation of his mother’s, Owen Putland Meyrick (pronounced ‘Merrick’), from whose family he inherited the Bodorgan estate on the Isle of Anglesey; hence he bore the unwieldy name Sir George Eliott Meyrick Tapps-Gervis-Meyrick. In 1856, the Bournemouth Improvement Act empowered a Board of Commissioners, and as Lord of the Manor he had a permanent place on it. The Board governed the town for the next 34 years, until the birth of Bournemouth Borough Council in 1890. By that time he, now usually known as plain Sir George Meyrick, had entered into the process of transforming these erstwhile turbary areas into local authority parks; it became a contentious issue which soured relations between Sir George and the townsfolk, but the matter was finally settled in their favour with the incorporation of the town as a borough in 1890, and from then on he co-operated fully. The first of the parks was opened in 1894 and was named Meyrick Park in his honour. It and the four other public parks were secured from development by the Five Parks Act.

Meyrick Park was opened on 28 November 1894 by Mrs Jacintha Meyrick, the wife of Sir George’s son – his own wife had died two years previously. The next day the 18-hole golf course in the park was inaugurated – the first municipally owned golf links in the country. It proved a great success, and its popularity led to many more. The course was designed by Tom Dunn, one of the great golf course architects in the tradition of Old Tom Morris of St Andrews. A Scot like Morris, he learnt his golf from his father, who played with and against Morris. Of Meyrick Park he wrote: ‘Nothing appeared on the surface of the land but heather, furze and pine wood; but with a hundred men, twenty horses and a scarifier, short work was soon made of this wilderness, and the links was completed in three months. It cost £2500.’

Dunn was appointed greenkeeper and professional, and he remained at Meyrick Park for five years, retiring only because of ill health. During that time he designed the Came Down links at Dorchester, which opened in 1896, and two years later the course at Broadstone, which he considered the best design of his career out of the 64 courses worldwide which are attributed to him. The Meyrick Park course, however, also has a considerable reputation, both for its scenic beauty and for its difficulty. The first hole, a 244-yard par 3, was once voted the hardest opening hole in the country, and the 14th inspired golfing great Henry Cotton to write: ‘There is no finer hole than that of the 14th at Meyrick Park.’

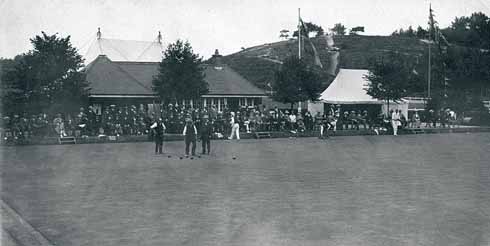

The course is more than three miles long and consequently takes up a large proportion of the park; but the Victorian predilection for sporting activities was further satisfied by the provision of a bowling green and playing fields. The bowling green was little used until 1903, when the founding of the Bournemouth Bowling Club increased interest in the sport. The club continues to flourish and is still based at Meyrick Park. The playing fields are currently marked out for rugby and have been used by Oakmeadians Rugby Club since 1988. But there is plenty of room for those with no sporting inclinations to enjoy the park – it was enlarged by the addition of part of the Talbot estate in the 1920s and is Bournemouth’s largest park, at 194 acres. Since it is still owned by Bournemouth Borough Council, there is no restriction on public access.

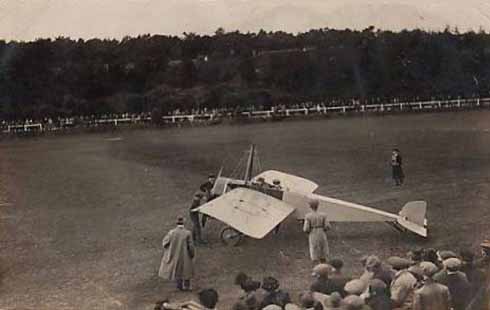

There is, however, one form of access which would not find favour today. On 8 April 1914 the pioneer aviator Gustav Hamel landed his aeroplane in Meyrick Park and gave the redoubtable Elsie Knocker (subsequently famous as a World War 1 nurse) a five-minute spin. He returned to the spot four days later and looped the loop twenty-one times, breaking the previous record for this recently discovered aerobatic feat. Alas, he went missing over the English Channel six weeks later.

Nowadays any excitement in Meyrick Park is firmly ground-based. Apart from sporting thrills, there is the annual spectacle of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra’s Proms in the Park every summer, with fireworks to round off each concert. The Meyricks from previous centuries would be surprised but probably rather proud.