More Questions than answers – The Tudor House

The Tudor House at Weymouth is one of Dorset’s historical gems that deserves to be better-known. Rachael Gower has visited it.

Published in April ’16

The reason why history is endlessly fascinating has a lot in common with why people like detective stories. Until a case is conclusively proved, it is an absorbing exercise to sift the evidence, to avoid red herrings and to spot a trail that might lead to the ultimate solution to the mystery. Weymouth’s Tudor House provides plenty of questions for amateur detectives and historians to puzzle over, but at the same time is a charming and unusual survival from five centuries ago.

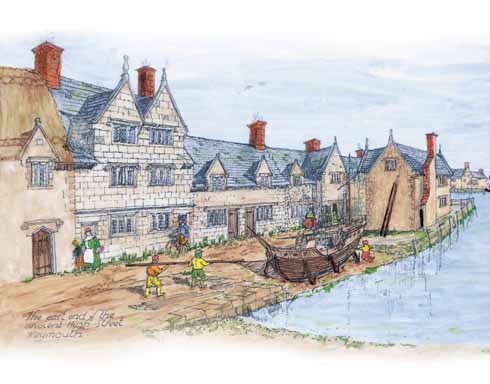

At least its date and the reasons for its location are known. Both architecturally and through the evidence of contemporary maps, it can be placed pretty close to 1600, just on the cusp of the Tudor and Jacobean periods. Today, its position some 100 yards from the waters of the harbour seems strange, but in 1600 it stood on an inlet of the harbour which would no doubt have had its own quays and wharves. For the house was almost certainly built by a merchant, taking advantage of the growth in overseas exploration and trade that was a product of Queen Elizabeth I’s largely peaceful reign.

He seems to have been a successful and wealthy merchant, too, for the house was constructed to what a modern builder would call a ‘high spec’, in Portland stone with a slate roof. The windows, for example, are comparatively large, which would have been an ostentatious display of affluence at a time when glass was a very expensive commodity. How did he make his money? Perhaps he exported the wool for which Dorset was famous and imported wine – years later, a wine merchant was using the house – but there is no hard evidence.

How the Tudor House now sits in relation to the waterside (beyond the end of the road at the right hand edge of the image)

A more intriguing question is why he built his home here, when similarly successful men were choosing to live further from the centre of town. A speculative but plausible theory is that the building served both as an office and as a home for a steward or manager and his family. Outbuildings, long since demolished, almost certainly were built as warehouses originally.

The purpose of the house changed dramatically in 1780 when the arm of the harbour on which it stood was filled in by public request. The 18th century was a notoriously malodorous time, but even the robust noses of those days could not stand the smell of an inlet full of the surrounding houses’ garbage and worse and probably with little tidal movement to flush it out. Deprived of its original purpose, the house was let in two halves, with a partition across the main room downstairs. The beam running the length of the room is a silent witness to the story. Not only can the mark of the partition still be seen on it, but the chamfering on its edge stops before the beam enters the wall by the original fireplace, whereas at the other end the chamfering continues into the chimney breast, showing that that fireplace was a later addition, installed when the room was divided. The beam also shows marks where it has been keyed for plaster on one side of the partition mark, but not on the other.

The western end in particular must have been very poky and was used as a shop, latterly as a greengrocer’s. By the 1930s the whole building was in a desperate state of repair and was in fact condemned by the local council. It was saved from demolition by two things: the outbreak of World War 2, which rather changed the council’s priorities, and local architect Ernest Wamsley Lewis. Wamsley Lewis had lived in Weymouth since childhood but moved to London to seek his fortune as an architect. He had some success, designing the art deco New Victoria cinema (now the Apollo Victoria Theatre), opposite Victoria Station, for the Gaumont chain. Like many a Dorset man, though, he found that the appeal of the capital paled against that of his home county and he returned to Weymouth. Taking a close interest in the town’s historical buildings, he formed a consortium to buy the Tudor House at the start of the war, but by 1945 he was the sole owner.

The six years of war had hardly improved the Tudor House’s condition, but Wamsley Lewis persuaded the council to let him embark on a complete restoration. The partition was taken down, a proper kitchen installed, the stone floors replaced with wood and the staircases improved; the one between the ground and first floors had disappeared altogether, possibly used as firewood by squatters during the war. It is believed that he also dismantled the frontage, numbering the stones so that they could be put back in exactly the right order.

The house was then let to a variety of tenants, ranging from student teachers to the actor, Peter Bull, who took it during the filming of Tom Jones, in which he played Dr Thwackum. He tells the story of returning to the house late one night with Albert Finney and two others, rather worse for wear, and crashing out in various states of undress. Unfortunately, a condition of some of the grants that Wamsley Lewis had obtained for the restoration of the house was that it should be open to the public on certain days and the following morning was one of those days, so the hungover thespians awoke under the curious gaze of a bunch of strangers.

The house guides dress in period costume for special occasions, like the Tudor Children’s Weekend with which the 2016 season opens

Wamsley Lewis’s other great legacy to Weymouth was the foundation in 1944 of the Civic Society, which inherited the Tudor House on his death in 1977. The society also received funds raised in an unsuccessful attempt to save another house of the same age on the harbourside. Within the Tudor House, Wamsley Lewis left a collection of Tudor and Jacobean furniture which is now scattered through the rooms. He had a good eye for an attractive piece, but it is frustrating that he left no record of where he bought them, so little information can be traced on any of them.

Leaving the main room downstairs, one climbs up to two rooms known as the Family Room and the Quilt Room. The outstanding feature of the Family Room is the painted wooden beam above the fireplace: another of the house’s mysteries. Is it original? Does it perhaps show some Dutch influence? Are the roses, which can still be clearly seen, a nod to the Tudor rose, or do they represent the Virgin Mary? If the latter, is the curled shape that can just be made out in the centre of the painting a serpent, representing evil? Or is it, more prosaically, a snail’s shell? The quilt room takes its name from a quilt that belonged to Wamsley Lewis’s grandmother. Too delicate to be kept out, it now hangs in a glass case, but a modern reproduction is on the bed.

Throughout the house are artefacts or reproductions to catch the visitor’s interest and to allow guides to introduce another aspect of Tudor life. This is especially so in the two rooms on the second floor, one of which has a rope bed cut away to show its workings, including a tool to tighten up the ropes – the origin of ‘Sleep tight’, perhaps? In the other room are a number of domestic items, including a table knife dated to 1500 and found in the mud of the river Thames in London; it was presented by a visitor who collected domestic silver, especially cutlery, because he was so impressed by what the Civic Society has achieved in the house. Also in this room is a 1623 book of homilies, mostly anti-Catholic, acquired by Wamsley Lewis, and a bobbin-winder for lacemaking; a very young recent visitor, befuddled by trying to comprehend what a gap of 500 years means, asked if it was a primitive CD player!

The table in the main room laid up for a Christmas feast, including a specially constructed boar’s head. The decorations feature holly and ivy, but no Christmas tree, streamers or glitter, all of which came well after the Tudor period.

In recent years, visitor numbers to the Tudor House have been static or declined, partly because fewer schools have the time and transport to make the trip and the Tudors are no longer part of the National Curriculum. A new curator has plans for special events and wider publicity to bring more people through the door, and anyone with an interest in the county’s history will hope that her efforts are successful – the Tudor House deserves no less. ◗

❱ The current opening times of the Tudor House are: May-October, Tuesday-Friday 1-4 and Sunday 2-4; November-December and February-April Sunday 2-4. Closed January.