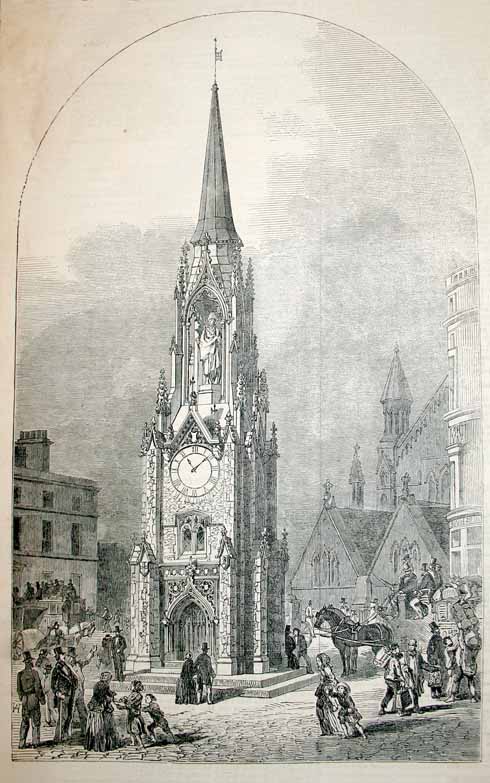

The Wellington clock tower

The story of one of the most curious of Swanage’s many curiosities is told by Rachel Gower

Published in March ’16

In the 1880s, Swanage was the fastest-growing town in Dorset, helped both by the burgeoning tourist trade and by the efforts of one man, George Burt. Swanage born and bred, he had joined the London building firm of his uncle, John Mowlem, which was responsible for many of the Victorian buildings that survive in the City and Westminster. True to his roots, Burt favoured Purbeck stone as a building material wherever he could, and this was the period when Swanage Bay was busy with ships being loaded to take the products of the area’s many quarries up the Channel and round into the Thames Estuary.

Designed and built to carry heavy cargoes of stone, those ships sailed skittishly when empty, so they would return to Swanage weighted down with ballast. For this purpose – and for the pleasure of glorifying his home town – Burt used stone and metal that had been removed to make way for new building. That is why bollards and lamp-posts all over Swanage carry evidence of their London origins and why the Town Hall looks so incongruously grand: its facade was part of the old Mercers’ Hall, designed by a pupil of Christopher Wren and brought to Swanage by Burt. But perhaps the strangest of all Burt’s objets trouvés is the Wellington Tower, which still stands between Swanage’s pier and lifeboat station.

The Wellington Tower was originally a memorial to the victor of Waterloo, erected by public subscription among the people of Southwark at the southern end of London Bridge. Local businesses, and especially the railway companies, also contributed to the cost. It was designed in the Perpendicular style by Arthur Ashpitel, an architect who built a number of churches in South London, Essex and Kent. The foundation stone was laid on 17 June 1854, two years after the Duke’s death, by Mr T B Simpson, who bore the resounding title of ‘Treasurer to the Commissioners for Lighting the West Division of Southwark’. The ceremony was ‘followed by an excellent dinner at the Bridge House Hotel’. The memorial was completed that same year, except that in a sense it was never completed because the original plan had been to incorporate a statue of the Duke. The funds raised did not stretch to that, and in any case, a fine equestrian statue of Wellington by the leading sculptor of the day, Francis Chantrey, stands outside the Royal Exchange, barely a quarter of a mile away.

The watchtower with no clock and no statue of Wellington, not to mention a different design of topping than the original spire

The London Bridge memorial was not just decorative: its lower portion was used as a telegraph station. The tower had another practical purpose because its correct name is the Wellington Clock Tower and it originally contained a clock with transparent dials, so that it could be lit from the inside. The clock had been made for the Great Exhibition of 1851 by Mr Bennett of Blackheath, who at the dinner after the laying of the foundation stone ‘took occasion to declare that the Clock which they had accepted was constructed with every improvement, and that he has undertaken to keep his gift in repair and complete working order during his lifetime’. He must have been kept busy, because the clock’s delicate mechanism could not survive the vibrations from the carts that rumbled by day and night, and it never kept good time. Ironically, punctuality was something of a fetish with the Duke of Wellington; tolerance was not his most notable characteristic, especially in old age, and he would surely have looked with patrician disdain on a memorial which did not serve its one practical purpose efficiently. When the memorial came to Swanage, the clock did not come with it.

So the monument on London Bridge could hardly be called a success story and the situation became worse when the view of it was blocked by the building of the Charing Cross to London Bridge railway and in particular – another ironic twist – by a viaduct that from 1863 carried trains into Waterloo East, named after Wellington’s most famous victory. It is worth remembering, too, that it was almost half a century since that victory, and memories of Wellington’s military glories had faded, even among those who had been alive during the Napoleonic Wars. Fresher in the memory was the Crimean War, which had finished in 1856 and was a much more unpopular war at home than is generally realised, so the celebration of martial glory was not altogether in tune with the national mood.

Most people in any case remembered Wellington as a statesman, who had been Prime Minister from 1828 to 1830 and briefly again in 1834, rather than as a military commander. He was deeply unpopular for his opposition to the Reform Bill – although he did support Catholic emancipation, perhaps because of his Irish roots – and on more than one occasion, rioting mobs smashed the windows of his London residence, Apsley House. In old age he was seen as a caricature of a crusty old Conservative peer, although some of his thinking was more advanced than he was given credit for.

So the Wellington Clock Tower was always something of a lame duck, in whose coffin the final nail was the pronouncement by the Metropolitan Police that it was an ‘unwarrantable obstruction’ to the increasing volume of traffic over the bridge. It was taken down in 1867, at the height of George Burt’s cannibalisation of London landmarks for the greater glory of Swanage, and was carried there as ballast in one of his ships, the Mayflower.

The plaque indicating the tower’s original lowly function as shipping ballast is appropriately enough only visible from the seaward side of the building

However, Burt presented the tower not to the town but to his friend and fellow-contractor, Thomas Docwra. He lived in a house called The Grove, which had been built by a Mr Coventry in 1836 and which Docwra had bought in 1866. Burt’s present of the tower was therefore a fairly remarkable house-warming gift and Docwra had it re-erected in its present position, which was then at the eastern end of the grounds of The Grove. The re-erection cost as much as the original building, and the initials and date ‘TD 1868’ can still be seen on the base. The tower would have pandered to Docwra’s taste for architectural curiosities; the Ionic pillars that now stand at the foot of Peveril Downs were originally sited in the forecourt of The Grove, which was later converted into the Grosvenor Hotel.

In Ashpitel’s original design, the tower had a rather handsome spire, but this was taken down in 1904. Today the reason is unclear; it was most likely because of storm damage, but some authorities maintain that the then owners of The Grove were ardent Christians who found it offensive that a secular building should be topped by so ecclesiastical a feature as a spire. Charles Harper’s The Dorset Coast, published in the following year, said of the monument, ‘Its tapering proportions are stunted by the substitution of a copper capping.’ Others have described the cupola that replaced the spire as ‘unfortunate’ or, less diplomatically, as ‘very like a dish-cover’.

So controversy dogged the Wellington Clock Tower throughout the first fifty years of life. Today it is more incongruous than controversial. If puzzled visitors seek information about it from one of Swanage’s more imaginative inhabitants, there is quite a variety of stories that they might be told, yet the truth is as strange as any fiction. What is certain is that the tower has become an established feature of Swanage Bay which would be greatly missed if it was not there. ◗