Let there be light… and power

Nick Woods looks at the past, present and possible future of energy and power in the Dorset landscape

Published in January ’15

Whilst most support the idea of renewable energy in the abstract, when it comes to the particular, many Dorset residents are concerned over the impact of large schemes, such as the proposed Navitus Bay Wind Farm, on the landscape. This scheme could include up to 194 wind turbines installed on the sea bed around 13 miles from Bournemouth and 9 miles from Durlston Head. The turbines, which could be up to 200 metres high with a maximum rotor diameter of 176 metres, are intended to generate enough electricity to power around 710,000 homes. Those for and against the wind farm have produced differing images of how it might look and what the actual visual impact would be once built is a matter of debate; it will certainly depend on the exact size, numbers and layout of the turbines were it to be built.

This “Prospect of Poole…” from John Hutchins 1774, “History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset” shows a windmill at Baiter

Exploiting the wind, and other ‘natural’ sources of energy is far from new. Dorset has around forty known or probable windmill sites. Hutchins’ History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset, first published in 1741, shows a windmill at Baiter in Poole. However, the only surviving historic windmill towers in the county are at Easton on Portland, both without their sails now.

By contrast, water power, probably introduced into Britain by the Romans, has left a more conspicuous legacy. Over a third of Dorset settlements in the Domesday Book of 1086 included a mill (the majority water mills) with a total for the county of over 250 mills. These generally were used to grind corn, but were also used in cloth and paper manufacture, saw milling and pumping water. Later, and indeed recently, some mills were converted to generate electricity for local use. Unlike large energy farms, even the sizeable number of old mill buildings remaining along the county’s rivers and streams generally fit harmoniously into the landscape.

In the early 1920s, only around 6% of British households had electricity; this supply was by and large from small, local (and, to be frank, often unreliable) power stations. Following the 1926 Electricity (Supply) Act, a workforce of 100,000 men was engaged to construct 4000 miles of cabling to connect 122 of the most efficient power stations in the country – the National Grid was created.

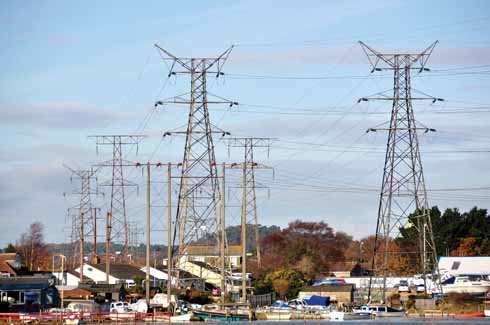

In a little over five years around 26,000 pylons were constructed. The ‘classic’ pylon was designed by the British architect, Sir Reginald Blomfield and the seemingly endless lines of pylons were controversial; their stark, giant outlines – ‘Bare like nude, giant girls that have no secret’ (as the poet Stephen Spender described them) have drawn criticism ever since. A major branch of the National Grid enters the county near Verwood, passes south of Dorchester and then runs roughly parallel with the coast.

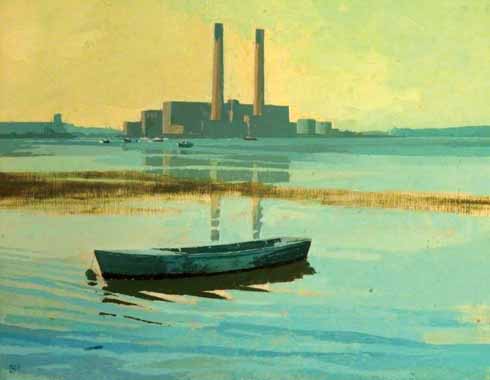

Once the Grid was established new power stations were linked in. Work on Poole Power Station began in 1946, with 250,000 tons of chalk quarried near Sturminster Marshall being used to reclaim part of Holes Bay. Eventually, the twin chimneys – rising to 325 feet high – would be an unmistakable land and seamark. The power station began generating in 1950 and could consume over 1000 tons of coal a day; the ash was used to reclaim what are now the playing fields nearby at Turlin Moor. The power station was later converted to run on oil and continued in use until 1984. In the 1990s it was demolished with the chimneys being blown up in 1993. With the recent construction of Poole’s Twin Sails bridge, development of the old power station site is likely to accommodate over 1000 new homes.

Dorset’s least obvious energy industry must be the Wytch Farm oilfield on the south side of Poole Harbour, the largest on-shore oil field in western Europe, which at its peak, in 1998, was producing 110,000 barrels a day. Most of the wells are screened by forestry. The oil and gas is transported by underground pipeline, and often the only clue to these is a marker post beside a re-planted section of hedge. An earlier proposal to build an artificial island in Poole Bay was abandoned as the then revolutionary ‘extended reach drilling’ was developed to reach out for over five miles under the sea. The most conspicuous sign of the county’s oil industry is probably the isolated ‘nodding donkey’ on the much smaller Kimmeridge oil field close to the coast path; this has been operating since 1960.

The United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority developed a 1000 acre research site at Winfrith Heath in the 1950s. Nine experimental reactor types were developed here, including some of the longest-running reactors in the world. Some also produced electricity for the National Grid, including the Steam Generating Heavy Water Reactor, which, after being switched on by the Duke of Edinburgh in 1968, generated electricity for over twenty years. Other hi-tech companies have moved into what is now known as Winfrith Technology Centre and the nuclear facilities on site should be fully decommissioned by 2021.

Roof-mounted solar panels are now a familiar (if not universally adored) sight. In the wider landscape, ‘solar farms’ are now being constructed with large arrays of panels installed directly on the ground. Thirty-eight planning applications for such schemes have been made over the last few years. One of the largest, at Mapperton Farm near Sturminster Marshall was approved by the local council in November 2013, but faced a judicial review in May 2014. This project will see the installation of up to 123,000 solar panels on 174 acres of farmland producing enough electricity to power around 6200 homes.

Exploiting the county’s energy resources has always had direct and indirect impacts on its landscape. Ruined water mills, the now departed chimneys of Poole Power Station, pylons and pipelines and the reclamation of parts of Poole Harbour are all consequences of our need for power. It is ironic that developing schemes to harness renewable energy, intended to reduce environmental impact, should have the potential to generate such strong concerns over their own environmental impact.

Whilst the nature of controversies over power generation may alter over time, one thing has not changed, the seemingly endless increase in the technology on which we rely in modern life. While we all enjoy the convenience of electricity, the competing claims of carbon footprints, energy costs, energy security and the broader visual environment will continue to generate arguments, although in terms of the character of Dorset itself, many fear that the industrialisation of the seascape and rural landscape is too high a price to pay. ◗