Cheese, pigs and vodka

Lindsay Neal on the Barbers: a family whose diversity of farming is unlike any other

Published in October ’14

Those willing to sound the death knell for farming can doubtless find plenty of ears to listen but, as ever, the true picture is never quite so straightforward. Closer inspection of the right places reveals the resourcefulness of the British farmer is as sharp as ever. Diversification is the name of the game as farmers rethink what they do and how they do it.

Whisper it who dares, there are even pockets of optimism out there in the green fields.

‘Plenty of good farmers have gone under, there’s no point in pretending otherwise, but this is the first time in my life that I’ve been able to think there’s a future in milking cows,’ says 46-year-old dairy farmer Jason Barber who keeps his 250-strong herd on land at Seaborough that his father Richard has farmed since the late 1950s.

The milk from his cows goes to make the famed Barber’s 1833 cheddar, produced on his cousins’ farm at Ditcheat, Somerset, home to more than 180 years of history that make the Barbers Britain’s oldest family of cheesemakers. The milk also supplies Ford Farm, the branded cheese made on the Ashley Chase estate at Litton Cheney. Its success stories include the award-winning Cave Aged cheddar and Coastal, America’s most popular imported cheddar.

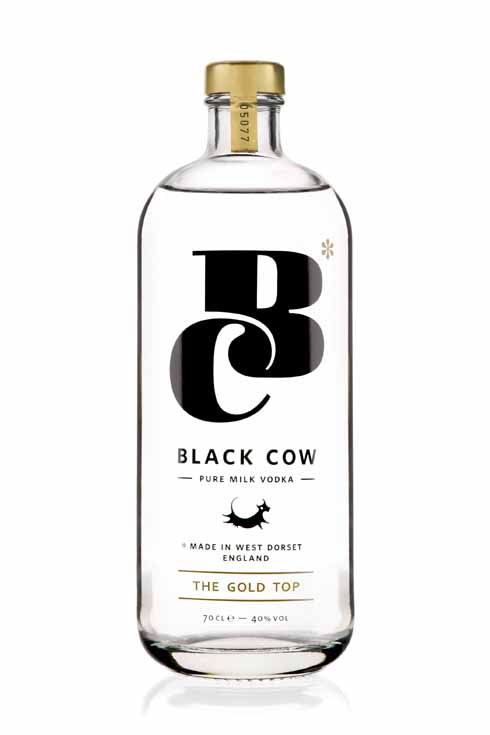

Cheesemaking produces plenty of the whey that is needed for Jason’s own exemplar of British agricultural innovation – milk vodka. Sold under the name Black Cow in a gold-topped (what else?) bottle, its crystal clarity and creamy character have excited critics and consumers alike, many noting how well it accompanies cheese, making it one of the most pronounced success stories of the emergent trend for premium produce and cosmopolitan localism.

That it’s a hit is no fluke. Not only does farming course through the Barbers’ veins – Jason’s brother Jeremy is an internationally renowned pig breeder – but so too does business nous. The boys’ father Richard long ago converted his cowsheds to stables and trained horses for champion trainer Paul Nicholls, including the Cheltenham champion hurdler Rock On Ruby . That enabled the cow sheds and milking parlour to be modernised for Jason’s cows and when fire destroyed Jeremy’s pig barn – and nearly 1000 animals – last year he overcame the tragedy to build a state of the art facility and is once again sending breeding stock all over the world.

‘My father diversified and made a great success of the horses because of his absolute passion for it. My brother diversified and he has the best pig stock in the world because he is totally committed to it. Black Cow was born out of my love for vodka, which was the only thing I could drink and still be able to get up and milk the cows in the morning,’ says Jason.

‘So yes, there is a need to diversify, but the most successful diversification happens as an evolution, not out of desperation. It’s harsh, but the farmer that sits with his head in his hands waiting for the idea that’s going to save his business is probably going to find it an uphill battle. Without the enthusiasm for the project and, it has to be said, the financial backing to cover the set up and get something off the ground, it’s very difficult.

‘There used to be seven farmers with herds in this valley alone, but now there’s just two of us – and that has happened in the last 30 years or so. ICI had three farms, but they couldn’t make them pay. Part of the land is now housing. Another farmer sold up and his land has been developed for holiday lets by an incomer. Another rents his land and another is running a caravan park and a bit of camping.’

For those that have survived, such as Jason, technology plays an ever-larger part in the management of their herds. The parlour process guards against infection and mastitis by disinfecting teats after milking and collars fitted with computer chips mean cows that need to have their food proportioned to how much milk they are giving while fresh calvers can be filtered out by a system of gates as they leave the parlour. Meanwhile, the heat generated by the cooling of the milk is reclaimed and that heat that comes from the compressors drives the refrigeration unit.

‘The milk business – I don’t do any beef – is OK as long as the price holds,’ says Jason. ‘We were fortunate in that we were able to bring in technology and expand the yield while improving the quality of the milk. Farmers that couldn’t afford to keep up with the technology also lost out as their milk wouldn’t have been up to standard.’

But for all the hi-tech jiggery pokery and digital monitoring of feed, there is still plenty of room for old-fashioned animal husbandry. Jason operates an on-going process of cross breeding with Swedish Reds and Fleckvieh bulls to strengthen his traditionally fragile Holstein Friesians and make them less susceptible to illness. He also knows a thing or two about their diet and how Dorset pasture is essential to the quality of their milk and, by extension, to the nature of Black Cow vodka.

‘If you just want white water you pump the herd full of cake, but milk from grass-grazed cattle is best for cheese-making because it is high in protein, so it has more solids in it and therefore more flavour. We get our herd outdoors and on the grass as soon as we can so they calf on grass from April until Christmas. The maize for silage is Dorset-grown and full of fibre so it produces sweeter milk. So in that sense Black Cow vodka wouldn’t be the same if it was made anywhere else but Dorset.

‘The process of making the vodka is all about extraction; the only thing added to the milk is the bacteria to make the cheese and the yeast to make the alcohol. The milk is heated to ferment it then vegetable rennet is added so the proteins form a curd, which separates from the whey. The curd is used for cheese, the whey can be spun to make butter and the whey proteins dried and sieved for baby formula powder, yeast can then be added to brew a beer, which is then distilled using our very secret blending and filtering process – that’s where the wizardry happens.’

Jason’s business partner in Black Cow is Paul Archard and together with Helen Watkins they have created and developed the brand. But as proud as he is of both the spirit and his herd, Jason is a slightly reluctant poster boy for either.

‘They wheel me along when they think it would be good for someone to meet the farmer,’ he jibes, then tells me they have recently done deals with Jamie Oliver’s Fifteen restaurant in Cornwall and the St Austell Brewery that will see Black Cow in its 3000 pubs in the west country. Dorset-based celebrity chef Mark Hix is also a big supporter of the brand and has created the ultimate dirty martini using Black Cow, as well as the Minty Black Cow, inspired by Moroccan tea; while Jason himself has contributed the Cos-moo-politan: ‘It goes on and on, so let’s not start!” he advises.

‘There are 50 new vodkas launched every year and yet they’re all over us because we’re the only one that’s different. There are businesses that have to be pushed and businesses that pull instead – Black Cow vodka is definitely a pulling business. Everybody we take it to loves the taste, the concept, the look, everything about it, so it is establishing itself very quickly.

‘But the businesses are run completely separately,’ says Jason before he gets too carried away. ‘The dairy has to wipe its face and so does the vodka. Neither subsidises the other – not yet anyway. Since I’ve been vodka making I’ve not had so much time for farming, but funnily enough now I’m actually enjoying the farming a lot more when I am out there. I still do the milking if I need to, but it’s only the last year or so that I’ve been able to stop and silaging in the wind and the rain is still a miserable experience – a nightmare in fact.’

Jason’s original plan was simply to make vodka and it took months of messing about with traditional methods using potatoes and grains before he tried milk and realised it was an almost instant hit.

‘Once we tried it on a few people we knew we had a product that would work, so in many ways its subsequent success hasn’t been a big surprise.’

Even so, before he could become the world’s first milk vodka farmer, initial production was delayed while Jason and his partners did battle with the local authority over whether or not its manufacture in a former ice cream works required a change of use, but the last two years have seen Black Cow make its presence felt in the wider world. Orders have been sent to Singapore and Russia and there’s interest from Malaysia and India, while the number of domestic outlets is growing all the time. There’s even Black Cow cheddar in the pipeline.

‘I love it, but to be honest we can’t keep much of it in the house because my wife Sally and I just polish it off,’ he laughs. ‘People really like it. I’ve even got my brother off the gin and on the vodka and my mum pops up for a Bloody Mary nearly every Sunday, but I can’t get my father off the red wine and whisky – although he has at last stopped calling me a ‘bloody idiot’ so I can at least savour that accomplishment!’ ◗