From Oshkosh to Swanage

Former GI John Livingstone recalls his wartime sojourn in Swanage

Published in August ’13

After several months of manoeuvres in Georgia and on Long Island Sound, my battalion took a two-week-long ‘cruise’ on a small passenger liner designed for three hundred passengers but converted to accommodate a thousand sea-sick soldiers. After zig-zagging across the Atlantic, we finally made landfall at the port of Avonmouth, where a blacked-out troop train awaited us. Six hours later we emerged bleary-eyed in the light of day. It was like coming out of a darkened movie theatre into the bright sunlight in my hometown of Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

We had not the slightest idea where our new home away from home was. We were told that, in our letters home, we could reveal only that we were ‘somewhere in England’, which was pretty much all we knew anyway at that point. Our battery lined up on the station platform in front of a big map of southern England, which generations of fingers had touched, and the well-worn spot revealed that we had arrived in Swanage.

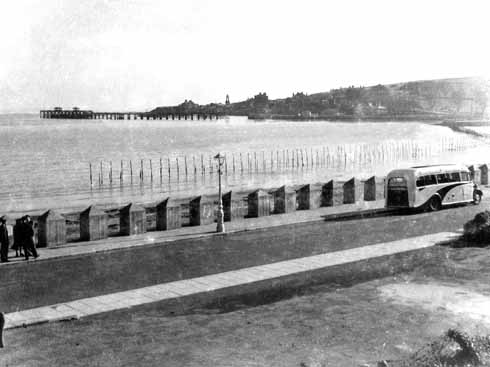

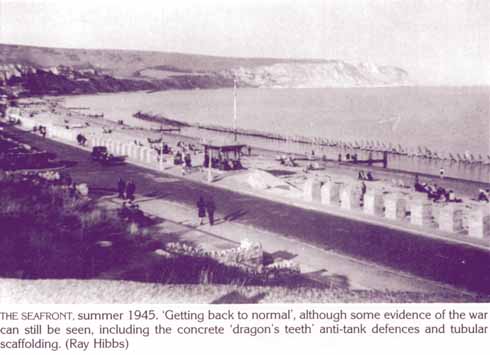

Swanage was then a Victorian-vintage collection of small hotels and bed-and-breakfast pensions, small shops and pubs that stretched along from a beach bristling with barbed wire and tank traps. To our eyes, it seemed quaint and the atmosphere on the dour side, particularly with the inhabitants having to cope with wartime shortages and stresses. Cold weather was already setting in; the days were getting shorter and the nights were getting longer and colder. In unheated pubs we soon acclimatised ourselves to warm British beer – and to keeping our overcoats on indoors to ward off the cold.

By early December, even more bitter cold had set in – the coldest winter in fifty years, we were told. It was so cold that the beer was freezing in the taps. With no central heating, my little billet – the Albany Court Hotel – might as well have been an igloo. The only source of heat for each two-man room was a tiny coal-burning fireplace and our own body-heat. There was plenty of coal available, but finding kindling wood to start the fires challenged every bit of Yankee ingenuity.

Overnight the ancient plumbing, served by water pipes exposed to the elements on the outer walls, would freeze and washbowls become temporarily useless. In desperation, American resourcefulness made use of the only kindling wood available: floorboards, stair railings, eventually some of the stairs, making it increasingly hazardous to run downstairs for the 0600 reveille down in the street.

Our mascot – Little Albert, as we called him, for he wasn’t more than three feet tall – was a Cockney boy who had been evacuated from London with his mother during the Blitz. They lived in a modest boarding house down the street from our even more modest billets. He lost no time in endearing himself to all as a kind of mascot for our battalion by showing up every morning to witness our reveille, and by teaching us several stanzas of a ribald Cockney song, ‘Yankee Soldier’.

One night, as Albert waited up for his mother to return home from a night of ‘pub crawling’ with our battalion sergeant major, he must not have appreciated what he saw through a crack in the front door where he lived. The next morning, as the battalion lined up in front of our billet for roll-call at reveille, Little Albert’s small figure marched up to our battalion commander, who was taking the

report: ‘All present and accounted for, sir!’ from the sergeant major.

Little Albert, tugging at our colonel’s trench coat, pointed at the sergeant major and yelled in a squeaky voice, yet one loud enough for all the world to hear: ‘Thar’s the bloke wot pruned me maw!’

No simultaneous translation from Cockney to American English was needed to grasp the essential meaning of his complaint. The entire battalion broke into uncontrollable laughter and hooted at a crimson-faced sergeant major, who vainly tried to quiet down the whole battalion. Our stone-faced captain – ‘Marblemouth’ Brundage – cracked a smile; even the colonel, his face as crimson as the sergeant major’s, couldn’t put an end to the mass laughter and chortling.

Post D-Day, some of the town's defences are removed as the country was no longer under the threat of invasion

One day, entering a chemist shop (what in Oshkosh we called a drug store), I met Mary Lloyd, a charming girl my own age. She and her mother operated the shop. Besides their usual stock of medicines and drugs, they still had a few picture postcards of Swanage and tourist mementoes available. It was frustrating not to be allowed to send home a local postcard, which would have ignited the fury of our unit censor. I soon got into the habit of buying those postcards anyway, planning to save them to bring home after the war.

Mary introduced me to her mother. They were devoted to each other, and worked well together. I never met Mary’s father, but gathered he was no longer in the picture, possibly serving in the Army, or a war casualty perhaps. I never broached the subject.

One evening, Mrs Lloyd and Mary invited me to join them for tea and ‘biscuits’ (‘cookies’, I was relieved to learn) upstairs in their tiny flat. Mrs Lloyd, probably thinking that all Americans were coffee drinkers, had taken the trouble to buy a bottle of syrupy ‘Camp coffee’ for that special occasion; I would much have preferred a cup of bracing English tea, but showed appreciation for her hospitable gesture.

Realising that Mary and I were becoming good friends, I saved enough of my monthly pay to ‘splurge’ a bit and take Mary for tea and watercress sandwiches at a pleasant tea-room near the beach. It was the first time I was able to be with Mary alone, and enjoyed our hour together as if it were forbidden fruit. I was looking forward to more close encounters of the English kind, but all too soon I was sent to a one-week course on mines and booby traps at Nether Wallop, a Nissen hut-dotted meadow near Salisbury, where I joined several more young unmarrieds – whom the army, in its wisdom, had selected for the dubious distinction of becoming the battalion’s mine and booby-trap experts.

The school was certainly nothing to write home about, even if I had been allowed to. My parents were already worried enough about my bringing home a British import if I survived being a forward artillery observer. That school, for all of its lethal curriculum, and even with the rusting Nissen huts, reminded me of an idyllic Constable painting. It paid to pay close attention to the instructor, not to let your mind wander off to Mary Lloyd during those lectures and demonstrations.

‘Stay off the verges!’ our instructors shouted at us as we drove along country roads. In English, this meant to stay off the soft shoulders of the roads, where mines could be buried out of sight. On ‘graduation night’ we faced a gruelling final exam, which consisted of crawling in complete darkness on our stomachs down a yellow-ribbonned lane, with mines planted a foot beneath the surface. We had to probe carefully with a metal rod until we felt the mine, then, with our fingers, slowly clear away the soil from the top of the mine in order to unscrew the detonator from it, rendering it harmless.

On my first attempt, I set off a small charge of TNT in the lane alongside me, which exploded with just enough force to make me never to want to repeat that mistake again: the Army’s version of ‘positive reinforcement’. The bang was immediately followed by a British Army sergeant, bellowing: ‘Troy hit agayn! This toyme, no mistykes!’

The next day, I returned to Swanage with a ‘Certificate of Completion’ to add to my army personnel file. I sensed a slightly elevated level of prestige among my peers as a brand-new mine and booby trap expert. No sooner had I signed in at my battalion headquarters when that same night, or more exactly at 0300, we were set to pack all our gear and load it into our Jeeps, and hitch our artillery pieces to our trucks. Our long convoy travelled through the middle of Swanage in driving rain, on our way to the port of Weymouth. The noise and clatter woke up most of the town, and its inhabitants rushed out of their homes, many wearing bathrobes or covering their heads with blankets, waving to us and shouting: ‘God bless! Stay safe! Come back!’

I didn’t see Mary Lloyd and Swanage again until some 25 years later, in 1970, when I moved my family to Esher, in Surrey, from where I commuted daily to London to ‘shoot’ Londoners for a photo-book. But that’s another story.

• You can read the full story of John Livingstone’s war (and Depression-era America) in his book The Importance of being from Oshkosh or view his award-winning photography at www.johnlivingstone.net