‘Finer than Salisbury Cathedral’ – Sherborne Abbey

Sherborne Abbey is one of Dorset’s most significant buildings, both architecturally and spiritually. John Newth has visited it. Photography by Jayson Hutchins.

Published in July ’13

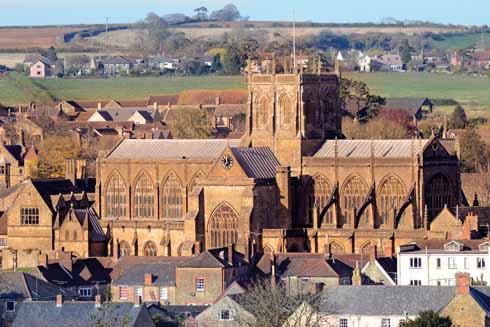

In 1823 the painter, John Constable, stayed with his good friend, John Fisher, vicar of Gillingham. During the visit, reported Constable, ‘Fisher took me a magnificent Ride to Sherborne: a fine old Town – with a magnificent Church finer than Salisbury Cathedral.’ Considering the enthusiasm with which Constable painted Salisbury Cathedral, this was high praise, but an understandable judgement on what many consider to be Dorset’s greatest ecclesiastical building. Perhaps Constable and Fisher walked up Digby Road towards Sherborne Abbey from the south, the best approach from which to appreciate the magnificent Perpendicular windows, the golden warmth of the Hamstone and the impressive tower.

It is likely that there was Christian worship on the site in Celtic times, but in 705, Aldhelm arrived as Bishop. He was, and remained, Abbot of Malmesbury, but was asked by his kinsman, King Ine of Wessex, to be a missionary bishop to the south-west. It was only forty years since the Synod of Whitby had resolved that religious practices in England should follow those in the rest of the Catholic Church, and Aldhelm brought the See of Sherborne into line with this decree: ‘By his preaching he completed the conquest of Wessex,’ it was said.

In 1075 the See was moved from Sherborne to Old Sarum and thence to Salisbury. Meanwhile, in 998, the then Bishop, Wulfsin, had established a Benedictine community which was to make its home in the Abbey until the Dissolution by Henry VIII in 1539. The nave of the Abbey also served as the parish church until the 14th century, when the separate church of All Hallows was built against the west wall. Relations between the townspeople and the monks of the Abbey were often strained, and in 1437 a row over baptisms led to violence, during which part of the Abbey was set alight; red marks on the stone of the Choir still show where it was scorched.

After the Dissolution, the Abbey was granted to John Horsey of Clifton Maybank. He enthusiastically took over its lands, but the building itself was of no interest to him, so he sold it to the town. All Hallows was demolished and the Abbey became the parish church once again.

The building we see today owes most to three 15th-century abbots: Brunyng, Bradford and Ramsam. That was the heyday of English Perpendicular architecture, the style that dominates the Nave and the Choir in particular. They are both famous for their magnificent fan vaulting, which the visitor can enjoy via mirrors on wheels. The vaulting does not meet in the middle, the gap being filled by a pattern of ribs with, at their intersections, bosses displaying heraldic emblems, subjects from nature and other devices; perhaps most famous is a mermaid with a mirror and comb, denoting vanity. The vaulting in the Choir, which is the earliest surviving fan vaulting on such a scale, is more ornate than that in the Nave.

Largely at the expense of the Digby family of Sherborne Castle, the Abbey was extensively restored in the 19th century. Too often this meant the disappearance of a church’s earlier features under a welter of misplaced Victorian over-confidence, but Sherborne Abbey was lucky that the work was in the hands of R C Carpenter and William Slater, who not only saved the Abbey from collapse but did so unusually sensitively. Carpenter later restored the tower, which is home to the heaviest ring of eight church bells in the world, the tenor alone weighing in at 2¼ tons.

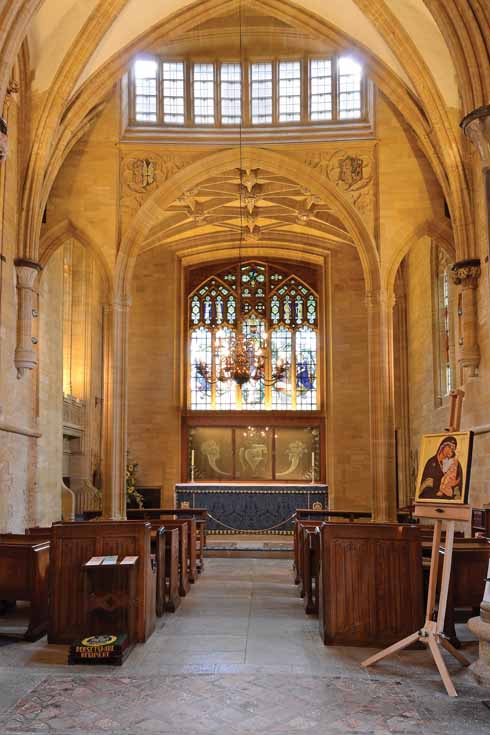

Columns and vaulting combine to glorious effect in the Choir. The glass in the east window is Victorian.

Also dating from the 19th-century restoration is most of the stained glass, the best of it in the Choir. The oldest glass is in one of the side chapels, St Katherine’s Chapel, and is medieval. Perhaps the most striking of the modern work is the superb west window, created by John Hayward of Corscombe in 1997 and celebrating the Incarnation in a riot of colour, predominantly blues and greens. It is strange now to recall the controversy when it replaced a rather undistinguished window by Augustus Pugin, whose Te Deum window in the South Transept survives.

The glass-engraver, Laurence Whistler, created the reredos in the Lady Chapel. It is perhaps not one of his more successful works, but the 13th-century chapel itself is a calm, intimate space after the grandeur of the Nave and Choir. At the extreme east end of the Abbey, it and the Chapel of St Mary le Bow alongside were for over 300 years incorporated into Sherborne School as the Headmaster’s house.

A church of such importance is naturally rich in monuments, of which three stand out. In the Wykeham Chapel adjoining the North Transept are the tombs of Sir John Horsey – he who grabbed the Abbey’s assets at the Dissolution – and of his son. John Leweston, who died in 1584, and his wife lie beneath the canopy of a splendid altar-tomb in St Katherine’s Chapel. Most striking of all is the memorial in the South Transept to John Digby, 3rd Earl of Bristol, who died in 1698, and his two wives. An important example of English Baroque, it was the work of John Nost, and the inscription notes approvingly that John Digby disdained ‘the Hurry of a publick Life’.

The Abbey has a long-standing association with the Dorsetshire Regiment and its predecessors. Thirty-eight Colours of the Regiment have so far been traced and they are all here, many of them in the Ambulatory between the High Altar and the Lady Chapel. The latest is the Colour of the 1st Battalion, laid up in 1964 when the Regiment was amalgamated into the Devonshire and Dorset Regiment.

Although there is an area, or suffragan, Bishop of Sherborne, he takes only his title from the place and he does not have a seat, or cathedra, in the Abbey in the way that a diocesan Bishop does in a cathedral. For the last twenty years the Abbey and its parish has been in the care of Canon Eric Woods, who has, he says, ‘the best job in the Church of England’. His team of largely ‘self-supporting’ (ie. unpaid) ministers also take care of the parish churches of Lillington, Longburton and Castleton and of ‘St Paul’s at the Gryphon’; St Paul’s is the church that serves the part of the town north of the A30, but when the congregation outgrew it, they moved to the conference centre at the Gryphon School and the original building became a community centre.

Like many large churches, the Abbey is used for non-liturgical events like concerts and plays. Canon Woods won’t refer to them as secular: ‘The divine can be discovered as well through a Mozart symphony as an oratorio,’ he says. The revenue from such events is a useful contribution to the ever-increasing cost of maintaining the building. A dozen years ago, masonry fell from the roof and it was discovered that metal reinforcement bars installed by the Victorians had corroded and expanded, while the elaborate vaulting in the North Transept is suspended from girders after it was found during a major restoration in the 1970s to be in imminent danger of collapse. Not all the maintenance is as dramatic as those two instances, but there is always some part of the Abbey’s fabric needing attention. Such continuing care ensures the survival of not only an historically interesting building but a majestic symbol of continuity and stability that serves the whole of Dorset.