Cordite, clay and calluna

Wareham’s northern neighbour, Sandford, is lacking in identity, but a new project is finding out more about its heritage and bringing the community together, as John Newth reports

Published in March ’12

If a town the size of Wareham may be said to have a suburb, then that role is filled on its northern edge by Sandford. Indeed, there is a suburban feel about the village, strung out as it is along the A351, with that excessively busy highway effectively bisecting the community. Because of its elongated shape and the dividing road, Sandford lacks a heart, both geographically and figuratively, and appears at first sight to be one of Dorset’s most amorphous and unattractive villages.

Now the Sandford Heritage project is setting out to correct that impression by discovering and providing more information about the area’s history and natural history. Its declared purpose is ‘to provide the opportunity for local people to find out about the cultural and natural heritage of Sandford’, but it also serves as proof that even the most unpromising-looking area has its own story to tell and its own attractions, even if these are not immediately obvious.

It had its beginnings in about 2006, two years after English Nature (now Natural England) took over the management of Sandford Heath from a speculative developer; although its name is rarely used locally, Sandford Heath is roughly the area to the east of the A351 between the roundabout by the middle school and the Holton Heath traffic lights. Natural England is a partner in the Urban Heaths Partnership, a group of fourteen organisations, ranging from local authorities through Dorset Wildlife Trust to the emergency services, which is funded by a levy on any developer who wishes to build anything anywhere near heathland. The partnership employed a Community Heathlands Officer, Roger Bell, in Sandford and it was he who first identified the potential for a heathland heritage project in the area.

By the start of 2011 everything was in place: a grant of £42,000 from the ‘Your Heritage’ programme of the Lottery, a part-time project officer in Wareham-based archaeologist and historian Ben Buxton, and office facilities provided by the Urban Heaths Partnership. The catch-line of ‘Cordite, clay and calluna’ was chosen. ‘Cordite’ is for the former Admiralty establishment at Holton Heath, where the propellant for naval shells was manufactured, because the geographical spread of the project is throughout the civil parish of Wareham St Martin, which includes Holton Heath, Organford and large tracts of Wareham Forest, although Sandford is by far its most populous settlement. ‘Clay’ is for the pottery industry, to which Sandford effectively owes its original existence, and ‘calluna’ is a botanical name for heather, which covers so much of the unpopulated parts of the civil parish. (The name is not genuine Latin, as it sounds, but was invented in the 19th century, based on the Greek word, ‘kallunein’, meaning ‘to sweep up’, a reference to the use of heather in brooms and besoms.)

But what does the project actually do? At the heart of its activities lies the involvement of the community in research and recording, and much has already been discovered about the history of the area. In the 19th century it was largely owned by the Digby family of Minterne. Why Henry Digby, one of Nelson’s captains at Trafalgar, should have wanted to buy a stretch of barren heathland so far from his home base is unclear, but he planted a large number of trees, some of which survive to this day along the A351. His name lives on in Digby’s Cottages, on the main road just north of Sandford First School, which are a 1980s replacement of the original.

Morden Bog and Old Decoy Pond. A typical heathland view in the area covered by the Sandford Heritage project (Ben Buxton)

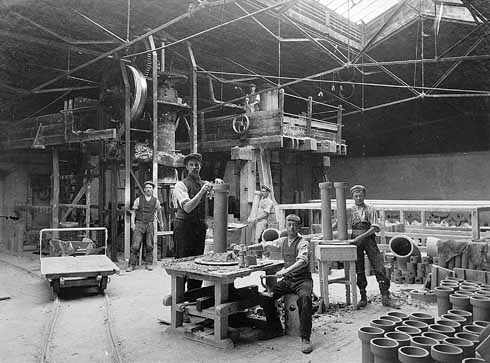

Apart from Digby’s Cottages, there were at that time only a handful of dwellings in what is now Sandford. That changed when the philanthropic heiress, Angela Burdett-Coutts, established a brick works in the 1840s to provide employment. Despite being named Victoria Works after the Queen, and supplying the bricks for the foundations of Crystal Palace in 1851, the enterprise foundered and was replaced on the same site by Sandford Pottery. This was built on the basis that the clay in the area was of good enough quality to produce fine china, but that assumption proved wrong and, after an equally doomed attempt to convert the works into a refinery for extracting oil from Kimmeridge shale, the pottery for the rest of its existence had to be content with producing mundane necessities such as drainpipes and chimney-pots. In 1966 it closed and the site, opposite the Sandford public house, is now occupied by the Forest Edge housing estate. Alongside the pub is the way known as Pottery Lines, which owes its name to the railway siding that crossed the main road from the pottery and ran down to join the main line.

The documentary research to fill in the details of these stories is being done by volunteers who were introduced to the Dorset History Centre by Ben Buxton and are now researching independently. Another example of their efforts is work on the route through the parish that would have been taken by a canal to join the English Channel to the Bristol Channel; only eight miles of this ill-fated waterway were ever built, all in Somerset, but the survey of the possible route gives useful information about land ownership in Sandford in the late 18th century.

The main research project actually on the ground has been the excavation of the ‘Roman Road’, the name given to the path that runs along the eastern edge of Sandford Heath, roughly equidistant from the main road and the railway line. A week’s dig was carried out, under the direction of archaeologist and Sandford resident Lilian Ladle MBE, and the result was that the Roman Road is not a Roman road at all! Rather it proved to be 18th-century, part of the old route from Wareham to Poole. The excavation also found flints dating to the period between 3500 and 6000 years ago when farmers began clearing woodland, a process which led to the creation of heathland. The diggers then moved on to Holton Lee, north of Holton Heath but still within the civil parish, to excavate a medieval house site found by Bournemouth University in 2000. Finds here included a hearth of burnt heathstone and a huge amount of pottery.

The project’s research has two more important themes. The first is the work on the natural history of the area. This is led by John Wright, who for years has been recording week by week the wildlife on the heathland in the project’s area. This labour of love continues, with the mild autumn and early winter of 2011 contributing to some unusual sightings, such as butterflies on the wing and grasshoppers in November. The second is the recording by trained interviewers of conversations with older residents of the area, some of whom have lived there all their lives. Eight interviews had been carried out by the end of 2011 and it is hoped that a similar number will be completed in 2012: they are priceless primary sources.

All this effort would be wasted if it were not communicated properly, and passing on the results of the research is at the heart of the project. This is done through the website but also by guided walks and other outdoor events in the summer and talks mainly in the winter. Particular emphasis is laid on the involvement of children and links have been established with local schools and youth groups. On one day last autumn there were 66 children running around the heathland, solving clues on a nature trail. Other events have included taking bat-detectors out on the Roman Road so that the children could find bats for themselves, and listening to recordings of German planes on the World War 2 gun tower that still stands on Sandford Heath. The most lasting means of communication of everything that has been discovered and achieved will be a book to be published when the two-year project winds down at the end of 2012.

The World War 2 gun tower on Sandford Heath, one of many defences of the cordite factory at Holton Heath, with bell heather in the foreground (Ben Buxton)

Ben Buxton’s job is to co-ordinate the work and to build a composite picture. ‘The cultural and natural heritage are part of the same story,’ he says. ‘The heathland was created by man by cutting trees and then keeping the land open through grazing. The clay pits became habitats for wildlife, and so on.’ His efforts and those of the project’s volunteers are not only unifying the story of Sandford, they are also helping to unify the community and to give it a sense of identity. Other areas in Dorset could do worse than to note its success and to take it as a model.

Sandford Heritage: Cordite, Clay and Calluna is based at the Urban Wildlife Centre, Beacon Hill Lane, Corfe Mullen, Wimborne BH21 3RX.

The website, created by volunteers, is www.sandfordheritage.org and the e-mail is b.buxton@dorsetcc.gov.uk.