Part of the Madding Crowd

Dr Ed Dutton reveals the lot of the Victorian Dorset shepherd and his family

Published in October ’10

Whether you are a Dorset native or whether your ancestors moved out of the county as agriculture declined, there is a very strong likelihood that one of your forebears was a shepherd. Thomas Hardy, perhaps surprisingly, wrote little about shepherds, preferring to focus on country folk higher up the village ladder. Far From the Madding Crowd’s Gabriel Oak – a shepherd with a small farm – is perhaps the nearest we have. It is apt that the novel’s title was taken from a poem which describes the departed ‘rude forefathers of the hamlet’ still somehow present, because even if your only connection to Dorset is enjoying the scenery, the ghosts of shepherds are everywhere. In Victorian England, Dorset’s fields would have been everything from places of barter to a kind of open-air dating agency. Milling with life, they were not far from the madding crowd.

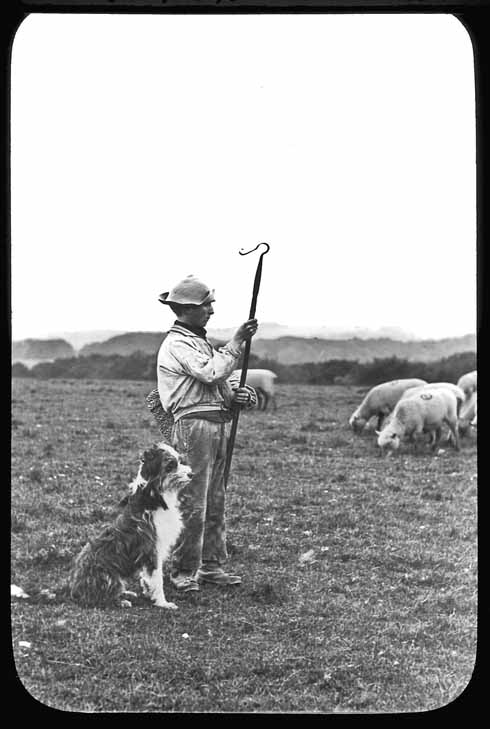

An idealised view of the country shepherd in his smock, this image from the Illustrated London News in 1883 is simply entitled ‘Springtime’

You had to like it being crowded if you were a Dorset shepherd. As Rev. James Fraser noted in 1867: ‘Their cottages are deficient of almost every requisite that would constitute a home for a Christian family in a civilised country.’ Shepherds’ thatched dwellings were usually semi-detached, with two families sharing between four and six rooms. ‘In the larger portion there is only one bedroom,’ writes the Rev. Fraser, clearly aghast. In addition, he observes: ‘there is no indoor sanitation and water is drawn from wells.’ In fact, conditions could be much worse even than that. In 1854, there was an outbreak of cholera in Fordington because people dumped their effluent in the same mill pond they used for water. In 1841, there were on average 36 people to a house in Milton Abbas – nine people per room. ‘[Winterborne] Kingston is a village where you may see open straight drains.’ reported farmer Malachi Fisher of Blandford in 1841 to the Commission on the Employment of Women and Children. The cottages were usually one up, one down with everyone sleeping in the same room.

Steel cages and concrete baths may have replaced willow hurdles and a hole dug in the ground, but the process of sheep-dipping is still clearly recognisable, here at Bradford Peverell

The shepherd’s diet was bland, although this began to change in the last quarter of the 19th century, when a cart would come to the villages once a week laden with tinned food, and better transport and imports pushed food prices down. Until the 1870s, though, shepherds’ families lived on what could be grown in their gardens – they might also keep pigs – and the little money they could scrape together to buy corn. A shepherd’s wife from Blandford described her family’s diet in 1867: ‘We live on potatoes, bread and, sometimes, pig meat…. We sometimes sit down to dry bread. We never have a bit of milk.’ They were lucky to get the ‘pig meat’. The shepherd would normally monopolise the family’s bacon, leaving the rest with bread, tea and potatoes and maybe some dripping.

We might imagine from Hardy’s novels that shepherds were solely hired yearly at fairs in different villages, but these were in decline by the Victorian era. Shepherds tended to stay on a farm, or a series of farms, for generations, moving only if the work ran out – or if there was better pay at another farm. The mid-Victorian agricultural depression saw migration not just to towns but also between Dorset villages. However, this was organised not just through hiring at fairs but also through advertisements.

Shepherds would work from dawn to dusk, often travelling for days with the sheep and having a ‘shepherd’s hut’ to sleep in. According to Mrs Bustle, a shepherd’s wife from Whitchurch Canonicorum in 1841, her husband would always spend part of his earnings at the nearest pub to where he ended up. Pay fluctuated according to farm, season and specific tasks, but £26 a year in the 1850s was about average for Dorset, lower than in the north of England. In the same period, a cook earned £40 a year, while an estate manager was on £80. However, the shepherd’s wage could be supplemented by perks: produce at reduced prices or even the occasional sheep. Experienced shepherds could command better money, and they had plenty of time to gain experience.

Shepherding was not quite a cradle to grave operation, but employers were keen to employ youngsters with experience, and their fathers glad to have the money coming in

From as soon as they could, the children of shepherds would work as agricultural labourers; boys often started as young as six. They might be employed to scare the birds off the crops or to help with the plough, which could interfere with muscle development and lead to bow-legs in later life. Parliament passed various poorly enforced laws, such as the act of 1890 banning work by children under eight. To do such work, children needed shoes and clothes. Leather shoes, which led to terrible blisters, were the shepherd’s biggest financial outlay on his children, as they lived rent-free. There were church-run village schools, at which shepherds were encouraged to have their children educated for a penny a week but ‘scholars’ needed shoes, too, so for the shepherd there was no financial benefit in educating children. Society perhaps benefitted, though; Pimperne’s Rev. Henry Austen reported in 1841 that the schooled children were better behaved and ‘kept out of beer shops’.

Benjamin Croft, a shepherd from Frome Vauchurch, had seventeen children between 1810 and 1839. Quite apart from the healthy exercise, this was just good economics because it left him in charge of an army of cheap labour, which was exactly what farmers wanted. They advertised in the Dorset County Chronicle for shepherds with large families. Many farmers insisted that the younger children started working, as they would then be ‘worth’ more by the age of ten. Mandatory schooling was enforced in Dorset in the late 1890s, as shepherds – perhaps understandably – could not be persuaded to send their children to school.

Girls worked either as servants, meaning they were more likely to learn to write, or on the farm, hoeing, threshing and gathering. In fact, claimed the 1841 report, this was one of the main ways that they would meet romantically interested young men because they would also be working in the fields. Rev. Fraser recorded that, considering their conditions, ‘I wonder that our agricultural poor are as moral as they are.’ Malachi Fisher pulls no punches. ‘In Milton Abbas the character of the population is decidedly infamous… Kingston is a village … where you may see pools of filth of all description and the character of the people is similar to these external appearances…. He also reports that the behavour of some women was a problem, especially in Stourpaine, because ‘in that village there are more bastard children than in any other village.’

In later years, wellies and waxed jackets replaced more traditional apparel, but the vigilant posture seems unchanged across time

Two of Croft’s children were illegitimate and his father – Benjamin Bridle Croft – was the ‘bastard child’ of a shepherd’s daughter and a yeoman farmer. At least, there was a 21 year-old yeoman farmer called Benjamin Bridle in Frome Vauchurch when he was born in 1753, and it was common to give a ‘bastard son’ his father’s full name. Illegitimacy was not the ‘shame’ that the gentleman farmers and vicars felt it should be. Fordington – and especially ‘Mixen Lane’ – was infamous for prostitution, alcoholism and pretty much every vice that 1850s Dorset had going.

But there was another side to shepherds’ lives. There is evidence of a strong sense of community, with the 1841 commissioners reporting that families sharing a cottage would ensure the ‘modesty’ of their children by arranging of all children of one sex to sleep in one room. Some shepherds skimped and saved to send their children to school, often because the church taught the ‘learning fitted for their station’ and left them religious and wanting their child to read scripture. If a shepherd could survive childhood, he would certainly live longer than a city-dweller. Benjamin Croft died in 1875 aged 86, his father lived to 78 and his sons into their 80s. Croft, like many old shepherds, relied on the Poor Law as he aged. By 1899, as farming declined, Dorset had 4 paupers per 100 people, the highest rate recorded in England.

We know from Hardy that some of the fields would have been alive with singing and folk songs, which were collected from talented shepherds in the late Victorian era. And Hardy seems to have met sensitive herders, if his portrayal of Gabriel Oak is based on reality, although contemporary critics were incredulous that a shepherd could be as articulate and thoughtful. In 1902, Hardy lamented that ‘folklore’ and ‘local knowledge’ had declined because more and more shepherds were migrating. Until about 1850, they had not moved far from what must have been like tribal homelands. By 1900, as people left the countryside, fit men could sometimes be in such short supply that they could charge what they liked. Hardy commented: ‘Their present life is almost without exception one of comfort. I could take you to the cottage of a shepherd… that has a carpet and brass rods on the stair-case… One labourer takes dancing classes in the neighbouring town!’

By 2009, a sheep-shearing marathon in Abbotsbury was such a novel event that it was worth an article in the Dorset Echo. A century and a half earlier, the county’s shepherds were regarded as somewhat less exotic, but we can understand a lot more about the county’s history if we understand them. It is a shame that the Dorset County Chronicle did not take the time to interview more of them in the 1850s when it had the chance!

[credits] 1, 2a&b Dorset County Museum; 3 & 4 Museum of English Rural Life